Getting kraken with GroundSource: How time-crunched news outlets reached their communities through texting

Getting kraken with GroundSource: How time-crunched news outlets reached their communities through texting

Written by Sara Catania for GroundSource and previously published on Medium here.

Many newsrooms talk about engagement, about connecting with communities they aren’t reaching, or deepening existing connections. Too often though they get stuck, and time is typically the named culprit (although time is just another way of saying priorities). They know what they’re doing isn’t reaching everyone, or forging deeper connections, but we just don’t have time to do more.

Two very different news outlets tackled the time problem head-on, each creating an engagement experiment limited to a single week.

Both news outlets powered their experiments with GroundSource, a messaging platform and service that enables direct, two-way connections between newsrooms and people, bypassing social media and other intermediaries. Both received subsidies to help fund the work, one from CLEF, the Community Listening and Engagement Fund, and the other from The Democracy Fund. The similarities end there.

In my role as chief storyteller for GroundSource, I spoke with both of these outlets about their experience. For the differences and the details, read on.

Outlet: Science Friday, aka SciFri, is a nationally syndicated caller-driven radio talk show and podcast with a weekly listenership of more than two million people across the U.S. and a mission to increase public access to scientific information. They have an active website and send out a dozen different newsletters as well as hosting events around the country and maintaining robust followings on Facebook and Twitter.

“We really want people to join in and interact in a meaningful way, and that was getting lost.”

Challenge: Each year, SciFri devotes an entire week of programming to cephalopods, the class of invertebrate including octopus, squid, nautilus “and all those smart, squishy things that live in the ocean,” as Brandon Echter, digital managing editor, puts it. Ceph Week, as it’s known, is incredibly popular with SciFri’s audience, and engagement always spikes when the conversation turns to the big-headed mollusks.

In the past, SciFri relied on social shares and Facebook live, but Echter says in recent months they’d started seeing a decline in engagement on those channels. “The algorithm is less chronological,” he said. “People would post something and no one would respond, or their response would get drowned out. We really want people to join in and interact in a meaningful way, and that was getting lost.”

He also noticed that on the existing social media channels, much of the interaction was coming from people based in New York or California, which didn’t reflect the show’s national profile. “We were talking among ourselves about this,” Echter said, “asking how do we deeply engage people in every part of the country.”

SciFri fans would receive a photo or gif of a beautiful sea creature that enabled the recipient to “share in their grandiosity.”

Idea: One thing the SciFri team knew from previous experience is that their audience enjoyed geeking out on fact cards, those “didjaknow?” nuggets of knowledge that are fun to share with family and friends. Ariel Zych, SciFri’s education director, loved the idea of a “Ceph of the Day,” wherein SciFri fans would receive a photo or gif of a beautiful sea creature that enabled the recipient to “share in their grandiosity.”

But how best to deliver these cards to the SciFri audience in a way that would deliver maximum impact without adding a lot of time and work for an already busy team?

As it happened, at the same the SciFri folks were brainstorming CephWeek they were getting their initial training with GroundSource, which they have access to thanks in part to a subsidy from the Community Listening and Engagement Fund. They realized that without expending too much additional time or resources, Ceph of the Day would be a great way to test GroundSource and deliver something meaningful to their audience. The bulk of the prep time was spent writing, and then re-working, the prompts delivered to the audience throughout the week so that the tone, length and content matched the texting format.

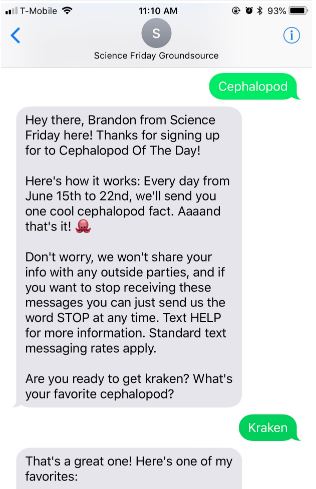

Execution: During the on-air CephWeek kickoff, SciFri shared the number and invited their listeners to text “cephalaopod” to sign up. They also promoted the sign-up on their website and social media, but based on the time of the signups they deduced that most folks texted in while listening to the radio show.

Each day, participants would receive a text and an opportunity to learn more, either by texting 1 for more facts, or 2 for a gif, or both, if they so desired.

The week kicked off with a Vampire Squid and the option for a “relaxing gif” of the creature bobbing gently along.

Some participants just wanted the gif, some wanted the fact and some wanted the gif and the factoids. Zych said any combination was good. “If people are using these cephs as a pleasant distraction from the goings-on of the world, then we’re providing a real service,” she said.

One of the worries was retention. Would the audience tire of Ceph of the Day before the week was through? The answer was a resounding no. On day five, the percentage of audience completing the entire texting chain of questions peaked, with the Cockeyed Squid.

Outcome: Based on behaviors on SciFri’s social platforms, as well as audience dial-ins to the show, Echter set a goal of 500 sign-ups for the GroundSource Ceph of the Day. The result was 60 percent higher — by week’s end, Ceph of the Day had 800 participants. Echter was heartened to see participation reaching beyond the usual concentration in New York and California, with audience in Kansas, Arizona, Florida, Ohio, and North Carolina, among other states.

Echter set a goal of 500 sign-ups for the GroundSource Ceph of the Day. The result was 60 percent higher — by week’s end, Ceph of the Day had 800 participants.

The experiment delivered some lasting benefits, in the form of a core group of participants directly engaged and ready for more. Of those who responded at the end, and stuck with the texting through the entire question thread, 88 percent opted to receive more texts from SciFri in the future, with access to more cool factoids and other stuff. “It was a great way for us to reach our core audience in a new way,” Echter said.

Ceph of the Day also afforded the SciFri team some new insights into audience behavior, Zych said. Depending on what they chose to experience, the audience split into those “coming just for visuals and quick entertainment and those coming to dive deep on a topic and learn.” With science literacy, she said, one of the most difficult things is measure is whether the audience has actually learned anything. “It’s a tough nut to crack,” she said.

At the end of the week, a subset of the Ceph of the Week audience took a short poll about their experience. Nearly all of the respondents said they learned something new, and 92 percent said they’d shared something they learned. “For us, that’s a home run,” Zych said.

One of the questions they’d like to explore more deeply is what they’re calling the “ultra passive” contingent of the audience, folks who texted in for the daily ceph but never engaged beyond that, a percentage as high as 60 or 70 percent of the total on any given day. “For us that’s a big mystery,” Zych said. And it also means “we better make sure that first text has purpose,” since it’s the only one that chunk of the audience is going to see.

Launching GroundSource with a finite test was a great way to introduce the tool internally, Echter said. He enjoyed witnessing the “a ha” moment among staffers when they got their first ceph delivered to their phone. “There was a lot of ‘huh! This is really cool!’ “ he said.

Outlet: 100 Days in Appalachia, run out of West Virginia University’s Reed College of Media in partnership with The Daily Yonder and West Virginia Public Broadcasting, was launched in the wake of President Trump’s election to counter the monolithic characterization of the region as “Trump Nation.”

Challenge: 100 Days brought in Jake Lynch, a Democracy Fund-supported community engagement editor, to explore ways to re-engage people across Appalachia in local reporting about their communities, and to reimagine how that reporting could happen. They agreed that one of the projects need to be aimed at attracting young people, as “news consumers, contributors and directors,” Lynch said.

Image courtesy of 100 Days in Appalachia.

Idea: To create the first-ever multi-state polling project on the political ideas and inclinations of high school seniors in Appalachia. The idea would be to execute it quickly and nimbly, Lynch said, with a minimal amount of time, and thus create a template that could be replicated in small, resource-strapped newsrooms that want to tap into youth voices. “It was a real goal of mine to make teenagers feel like they’re an important part of the political and social conversation,” and to not just treat them like a homogeneous voting block on certain issues” Lynch said. “So it felt like we were entering interesting ground with the polling that we did through GroundSource.

Execution: Lynch wanted to make the project classroom-based, and the hardest part was finding teachers to participate. “It took some convincing as to why they should make their students available for something like this,” Lynch said. “In some instances we had principals saying I’m not really comfortable having my students give responses about gun control or about protesting or anything like that.”

However, he said most of the reluctance stemmed from the fact that the schools didn’t know about 100 Days in Appalachia, and they didn’t know him. “If you were a local newspaper or a local media organization wanting to do this at a local high school where you already had relationships,” he said, “it would be a snap.”

Ultimately, teachers in seven schools in West Virginia, Kentucky, Virginia and North Carolina agreed to post a question in class each day, giving students a few minutes to text their responses. Lynch printed the questions on a sheet of paper (modeled on the work of Jesse Hardman, the creator of the Listening Post in New Orleans). There was no texted prompt. Instead the prompt was initiated by the teacher and the poster. The kids then texted the number with the keyword, which generated question number one. The first question was a yes or no, and then depending on the response the students received an open-ended follow-up question. After that they received a thank-you message. “It was short and to the point,” Lynch said.

Over the course of the five-day project, students weighed in on whether they thought their vote could make a difference in shaping society, whether they identified with either of the major political parties, their thoughts on gun control, whether they had attended, or might attend a political rally or protest, and what issues were important to them.

“I encouraged the teachers each morning to say hey, take a couple of minutes and use this as a teaching exercise,” Lynch said. “It seemed like a good majority of the teachers did that, instead of saying do your texting now and let’s get on with it. I think it generated some conversation before and after the texting process.”

Image courtesy of 100 Days in Appalachia.

Outcome: The response rate throughout the week was consistently high, Lynch said, with nearly all of the 90 students across the classrooms participating each day (the exception was one day when two of the classes were on a field trip and participation dropped to about 50%).

“I intuitively suspected it, that the kids would feel comfortable using texts to respond to questions like this, and this proved it to me,” Lynch said. “Responses came through really quickly.”

As part of Lynch’s agreement with the teachers, each of them was given access to their students’ responses, and in one case he spoke with the teacher about sharing the content with the student newspaper.

Lynch found a couple of the top-line responses “really surprising”: while nearly a third of respondents said they did not “strongly identify” with one of the main political parties, nearly two-thirds said they are optimistic their vote will make a difference in shaping society.

On the question of gun control, 45 percent identified guns as an issue they are concerned about (from all perspectives), and 55 percent said they were in favor of stricter gun controls. The economy, abortion, and the environment also received multiple mentions.

About a quarter of respondents said they had attended a rally or protest in the past 12 months, and of those who hadn’t nearly two-thirds said that they would, given the right issue, and/or that rallies and protests have value.

“I can certainly imagine it being very easy to do on a continued basis.”

As far as creating a workable template for small newsrooms, Lynch says the experiment was a success. “I’ve worked in small newsrooms and I’m picturing what this would look like,” he said. “On a Monday morning I would just drive down to my buddy at the local high school and say hey, let’s put together a list of questions and then over the next six months we’d just do it, even if it’s only one a month. It takes less than an hour’s worth of work to generate genuine, insightful content. I can certainly imagine it being very easy to do on a continued basis.

“What I love is being able to see an open-ended response that one of the kids has given, and by looking at that sentence or two I can tell, this kid’s got something to say. So it would be very easy to text them back and say hey, I’m the reporter that was talking to you about such and such, would you mind, could we chat I’d love to learn more. It beats the hell out of wandering around a school trying to find kids that have got something to say.”

“I think its simplicity is what made it work,” Lynch said. “A phone, a classroom, and three minutes once a day.”